On March 3, a bill aimed at barring transgender women and girls from participating in school athletic competitions designated for females failed to advance in a divided Senate.

Regardless of where you stand, I wouldn’t be too quick to proclaim victory or tuck tail in defeat—it’s just one outcome in what’s sure to remain a confusing, contentious debate.

Maybe we can cut through this mess and make some sense of it. Let’s break it down.

What dog could you possibly have in this fight? You’re a cisgender dude from West Virginia who writes about weight training for an audience that’s most likely comprised of a bunch of other cisgender dudes. You probably drive a pickup truck and listen to twangy music!

Hey now, I resemble that comment! But you also don’t know all there is to know about me.

I had a daughter named Ruby. And although she died far too young, I still see myself as her father. I often think about the messy world she’d have grown up in and the values I’d have wanted to convey to her.

When she passed, she was still in that androgynous little kid stage. She might have been playing gently with her stuffed animals in one moment. A minute later, she may have tossed them aside to roughhouse with me instead. Depending on the scene someone observed and their preconceived notions, they could’ve assumed she was either sex.

As she grew up, maybe she’d have had classmates with gender identity issues. Or maybe she’d have been the one with confused feelings about who she was. As a bereaved parent, I know all too well how most of us have this unjustified optimism that we’ll escape life’s most difficult problems, yet none of us get through unscathed.

Whatever she may have faced, I hope I’d have loved and supported her unconditionally, but I’ll never know for certain how I might have reacted. Ah, what I wouldn’t give to have her back, gladly embracing any obstacle in exchange for more time with her.

Instead of indulging in impossible fantasies, the best I can do now is lend a reasonable perspective to problems I no longer have to worry about facing.

In that spirit, let’s put aside liberal and conservative political labels for a minute, look at the plight of transgender athletes as rational people, and see if we can find any common ground. Maybe that’s a fantasy, too, but hope springs eternal in the deluded.

Assuming you’ll let me slide on the credibility issue, can I share my so-called “novel” take? It’s about the distinction between intersex and transgender.

I keep thinking about a particular sub-issue on which we might be able to agree. Keep in mind that I’m not a medical doctor or scientist. I’m just a person who thinks we’re oversimplifying when we lump intersex and transgender people into one group, as both governing bodies and the general public typically do when considering athletic eligibility.

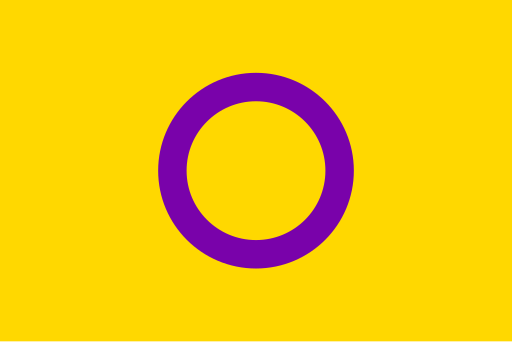

First, a little layman’s review of the terms. Intersex refers to individuals born with variations in their sex characteristics, such as chromosomes, gonads, hormones, or genitalia that do not fit typical definitions of male or female. Transgender describes individuals whose gender identity differs from the sex they were assigned at birth.

While some intersex people may also identify as transgender, they’re distinct experiences. Those distinctions seem particularly relevant to the athletic eligibility debate.

Transgender people who transition are making that choice and have to live with the consequences. Those consequences might include being ineligible to compete as a member of the gender they transition to—especially if they have, or are likely to have, a significant competitive advantage based on their biological sex.

Fairness, after all, isn’t just about the right to compete. It’s also about creating a level and safe playing field, at least insomuch as possible, given the range of expected variance in human ability.

As a father, that logic makes sense to me. If my daughter were at an increased risk of injury because of someone with masculinized physical traits (size, strength, aggression, speed, etc.) beyond what they might receive in the genetic lottery as a biological female, I’d object.

Selfishly, even if it were just that her chances of being competitive, winning, or earning a scholarship for being good at her sport were reduced, that wouldn’t sit well with me either.

Okay, I’m following your rationale for excluding transgender athletes, even if I disagree with it. So what sets intersex athletes apart, in your opinion?

People born intersex haven’t made a choice that gives them their advantages. They just don’t fit neatly into traditional gender categories. Their situation seems trickier.

Should they be excluded from competing altogether because of a difference over which they had no control? Sorry, you don’t belong on any of our teams. Take your ball and go home. Surely, we can do better as a society than that.

How many intersex people even want to participate in sports? Are we talking thousands or a handful (it matters when considering the impact on competitive balance)?

I’m guessing they don’t benefit from similar hormonal advantages as males who transition to female after going through puberty. Even without masculinizing hormones, however, they might have structural advantages common to biological males, such as size, bone density, and tendon/ligament attachment points.

Is there any way to quantify the impact of those characteristics? Maybe intersex individuals competing in women’s sports have no advantage over other women who also excel at sports and presumably possess the same physical attributes to a greater degree than average females.

If that could be proven, then there’s no reason left to exclude them—unless all along, the rejection was more about spite and fear than fact.

Your argument seems pretty cut and dry—trans out and intersex in. Is that it? Where do we go from here?

I don’t know the answers to all the questions I’m asking. I’m not sure anybody does. I haven’t found many other people who have even asked them.

I also don’t mean to be insensitive to either group. Being born feeling like you’re in the wrong body may not leave much of a “choice,” either.

Earlier, I wrote about the importance of creating a level and safe playing field. I also qualified my statement by saying, “insomuch as possible, given the range of expected variance in human ability.”

The best athletes have always run faster, jumped higher, and hit harder. They’re born that way. Although it’s not quite the same, intersex people who might have a competitive advantage are also born that way.

If we’re going to find any common ground, why not start with them? They may have some genetically acquired edge, but it may not be nearly as pronounced as males who transition to female have over biological females.

I’ll close by returning the science to scientists and touching on the human element of the discussion. I’m thinking now about where we are collectively as a society in our readiness for change.

Equal rights for any marginalized group don’t happen all at once. They evolve as discourse and public perception gradually change.

Separating the two groups, the question of eligibility of intersex athletes seems to me to be somewhat less politically charged than the plight of transgender athletes. Dare I say, it might also be more open to an appeal to simple decency.

Leave a comment