“On the eleventh day of…” Okay, okay, I’ll stop. Despite my festive mood, forcing an analogy with The Twelve Days of Christmas isn’t working. What is working, and has been for about seven decades now, is Bridgeport football.

We just picked up our eleventh state championship in dominating fashion. These triumphs often lead to arguments over which team was the best, as if there’s some football nirvana where the 1986 squad could test its mettle against the 2000 juggernaut, etc.

Until artificial intelligence evolves much further, we’re not settling that debate, but there’s something we can do that’s just as fun: We can take a trip down memory lane to celebrate them all.

So grab a cup of hot cocoa and curl up in your favorite armchair by the fire, and we’ll revisit some Indian magic, with visions not of sugar plums, but of footballs, dancing in our heads.

State Champions

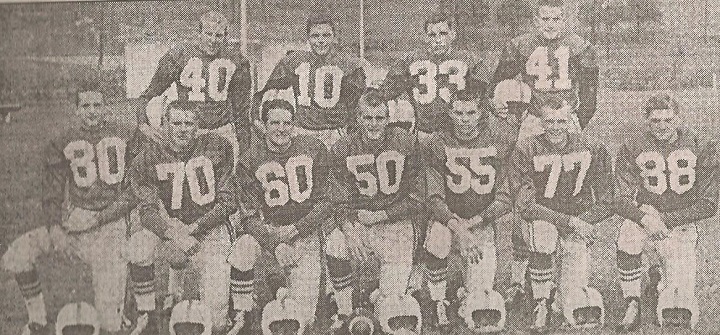

1955

We won our first state championship fourteen years before I was born, and this is the team I know the least about. Here’s something I do know: the first time you achieve any milestone is generally the hardest because you’re venturing into uncharted territory.

This trailblazing group did it to the tune of four shutouts along the way and a convincing 45-13 championship victory over Webster Springs. Never forget where you came from or who you owe a debt of gratitude.

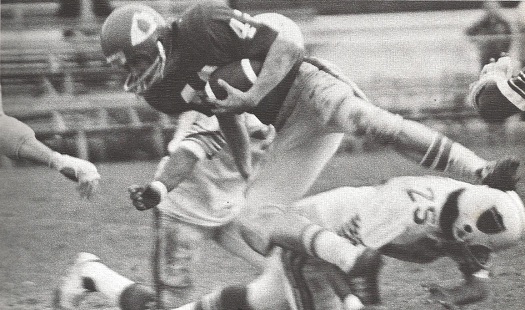

1972

Growing up, one name was synonymous with Bridgeport football: Steve Stout. Even today, anytime anyone is ticking off names of the best players in Indians’ history, Stout’s is mentioned early. All these years later, he’s still second on the all-time rushing yardage list.

Add in five straight shutouts to begin the season (seven in all), the fact that the 1972 team played up in Class AAA despite an enrollment that would have qualified them for Class AA, plus a playoff format that saw only four teams in each classification make the tournament, and the mystique surrounding 1972 remains to this day. Even more than fifty years removed, Indians’ faithful will never forget the narrow 18-16 playoff victory over Saint Albans or the 16-14 championship over DuPont that was decided by a two-point conversion pass.

1979

I question the veracity of my memory of being at the 1979 state title game at Laidley Field in Charleston. I’d have only been ten years old, and my sister just six. And my single-parent mother would have had to have driven us there alone. Still, I remember it.

I also remember a group of players visiting my classroom at Johnson Elementary, and I know that one’s true. In my young mind, Charlie Fest, Brad Minetree, and Bobby Marra may as well have been Pittsburgh Steelers. And in Indian lore, they’re still revered.

With a 10-0 regular season and six shutouts, the 1979 team hit all the marks of greatness. There’s also the 7-6 playoff win against the formidable Parkersburg Big Reds—still the program that’s won the most state titles with a staggering 17. Bridgeport never throws, but who can forget the iconic image of Minetree catching a drive-extending pass from Marra over the outstretched arms of a Parkersburg defender, mud streaking both their forearms as they reached skyward?

Another of my strange 1979 memories is of the Parkersburg mascot dressed in full Native American war regalia jamming a spear into the frozen ground in front of our sideline before the game. Did that happen, or is it just part of the legend that grew out of my childhood memories?

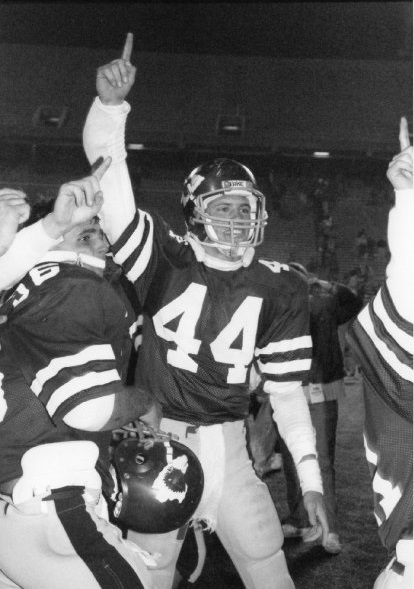

1986

One minute you’re so young you don’t remember which of your memories are fabricated and which are real, and the next, you’re buckling the chinstrap on that helmet with the coveted arrowhead on the side for the final time.

Our Christmas time machine has arrived at the team I played on now. It was Coach Wayne Jamison’s third state title and the one that cemented his legacy as one of West Virginia’s all-time greats. For years, I thought Bridgeport’s success was all about Coach Jamison. I still do in many ways, but we’ve gone on to win championships under the direction of four other coaches, so there must be some other reason, too.

Maybe it’s the players, and I played with some good ones. Nearly all of the toughest people I’ve ever met are from right here in my hometown—All-Staters like Scott Creak, Anthony Napolitano, Tim Randolph, David Wright, and Ryan Skidmore.

We won our first three games by scores of 35-13, 42-0, and 42-0. And then we lost one of our best running backs, Clarence Hardy, for the season to an injury. As he was our only real threat to turn the corner and take one the distance, the rest of our games were low-scoring “slug-it-out in a phone booth” affairs.

Fortunately, we could lean heavily on a stingy defense that pitched five shutouts and never gave up more than thirteen points in any game. Even so, we lost one along the way, an uncommon moment of adversity among Bridgeport’s title-winning teams, but we had the resilience to overcome that loss.

All three of our playoff victories were uncomfortably close. In the first round, Magnolia returned the opening kickoff for a touchdown that might have shell-shocked a lesser team. Instead, we battled back and beat them 21-13. In the next contest, we narrowly escaped against the previous season’s champion, the talent-laden Winfield Generals, by a slim 10-8 margin.

It took a 39-yard, final-play field goal from Scott Lewis, one of the first in a long line of excellent kickers poached from the soccer team, to secure a 10-7 championship victory over the Jed Drenning-led Tucker County Mountain Lions. Drenning, who we held in check throughout, won the Kennedy Award, West Virginia’s most prestigious football honor. During his college career, he became the first West Virginia Conference player to accumulate 10,000 yards of total offense playing for Coach Rich Rodriguez at Glenville State College.

Scrappy. If you ask me to define the 1986 team in a word, that’s the one I’ll pick. We were going to fight you until the final whistle, and maybe out in the parking lot, too.

1988

The greatest game in school history and perhaps the best ever played in West Virginia—that’s the legacy of 1988. If you weren’t there, you probably assume I’m exaggerating. If you were at Mountaineer Field like I was, dragging my Uncle who was visiting from the DC suburbs for Thanksgiving and had no real ties to Bridgeport besides my family, then you know.

As if five regular-season shutouts weren’t enough, the 1988 team terrorized playoff opponents East Bank and Musselman with two more by scores of 22-0 and 35-0 before facing old familiar foe Winfield in the final. Most great champions have a worthy adversary to measure themselves against. Think of Ali and Frazier, the Pittsburgh Steelers and Dallas Cowboys, and Wile E. Coyote and the Road Runner.

In the 1980s, Bridgeport’s Wayne Jamison had Winfield’s Leon McCoy, an early weight training innovator and the winner of over 200 games and Class AA state football titles in 1985 and 1987.Deadlocked at the end of regulation, the two teams would trade haymakers for a staggering four overtime periods, each firing and matching the other’s best shots on short, twenty-yard fields by rule.

I interviewed Coach Jamison for an article that was published in Wally & Wimpy’s Football Digest (a fantastic little weekly publication that you could grab for free at Go-Mart) back in 2000 and reprinted on Connect-Bridgeport in 2020. I mentioned to Coach that he’d often said, “Three things can happen when you pass and two of them are bad.” He swiftly corrected me, saying, “It’s actually four with three bad outcomes.” I’m not sure what third catastrophe he had in mind, but to say he didn’t like to take risks would be a colossal understatement. He didn’t even like to pitch the ball, never mind throwing a forward pass.

So when his exhausted team lined up to kick the extra point that would force a fifth overtime, the call he made was perhaps the most unexpected and brilliant one I’ve ever seen. Holder Pete Curry, a backup quarterback, received the snap, popped up, and lobbed a perfect pass over Gary Lhotsky’s shoulder near the back left corner of the endzone. Just like that, the greatest game I ever saw had ended, our fourth state championship secured by a sliver-thin 29-28 margin on the most daring play call I ever saw—and the kid who sat a couple of pews in front of me in church every Sunday growing up had caught the most important pass in our long history. Even my Uncle agrees.

2000

Unexpected dominance, that’s what I remember most about 2000. If you’re from Bridgeport, you can’t help but start to expect to win, except that we’d been slightly off throughout the nineties. We still made the playoff field most years, but multiple regular-season losses and early exits became more common. Perhaps there’s a lesson there in complacency and taking winning for granted, or maybe it’s just that doing it as consistently as we’ve become accustomed to is damned hard.

With a 7-4 final record and a rare first-round playoff exit as the higher-seeded host, 1999 was a mediocre season by Bridgeport’s standards. So I didn’t see it coming when we opened 2000 rolling over opponents by scores like 55-12, 59-14, and 42-7. The dominance continued through a 10-0 regular season in which we were only tested once, by our crosstown nemesis, Robert C. Byrd, in a 7-6 cliffhanger that Connect-Bridgeport Administrator Jeff Toquinto called the greatest regular season game in BHS history. Lopsided playoff scores the likes of which I’d never seen us post before went like this: 48-8, 42-12, and 42-7.

Standing in the way of a championship remained only the Wayne Pioneers, a program often near the top of the Class AA heap. This would be our first title game tussle with the southern West Virginia powerhouse, but not our last. My Uncle and I were back on the road for the first time in 12 long years, this time to Wheeling, and I was excited. He was… well… let’s just say he was a good sport.

At that time, the Class AA game kicked off championship weekend on Friday evening, and you could count on cold weather. We left in time to stop for dinner at a local diner. When our waitress cleared our plates, she did a double-take at the fifteen empty sugar packets next to my Uncle’s iced tea. Or maybe it was a second glance at him—the old man still had game, and his evening was improving by the hour. It continued improving, especially for me, throughout the actual game. Despite a tight 14-6 final score, the impression I’m left with today is that we were in control throughout, the outcome never really in doubt.

My fondness for this team is intertwined with memories of my Uncle in his Russian ushanka hat, pouring hot coffee from his thermos to stave off the cold. This year, as I pulled on my BHS 2000 state champs toboggan before our semifinal victory over Fairmont Senior, I was reminded of the perfect evening we spent watching the Indians close out a perfect 14-0 season twenty-four years ago.

2013

From 2009 through 2015, we played Wheeling Park every year and went 3-3-1. More on that tie later. In those seven games, the margin separating the two teams was never greater than four points. In 2013, we opened our season with a 47-28 victory over Buckhannon, in which we gave up more points than I thought we should have, and then lost to Wheeling Park 14-17. I followed the team closely, as I do most years, and this slow start had a lasting impact.

Thus, when we later twice posted over 60 points and shut out three other opponents while scoring over 40 points in each game, I didn’t trust my eyes. Even a playoff march that saw us steamroll Roane County, always-tough Fairmont Senior, and a Bluefield program that’s had as much championship success as we have, didn’t fully sway my opinion. Just like our 2000 season, we would face a talented Wayne team that had rolled through their schedule as convincingly as we had. I was concerned it might not go our way.

On championship weekend, my then-girlfriend/now-wife Christina and I were vacationing on the Hawaiian island of Maui. Thankfully, we also traveled with a friend of hers, providing her with someone to chat with while we made the 37-mile drive from sea level to the 10,023-foot summit of gorgeous Mt. Haleakala. I was too busy holding my phone to my ear so I could listen to internet radio coverage of the game to be much of a conversationalist. It didn’t matter where I was; a piece of me remained with my Indians playing over 4,500 miles away in a driving snowstorm.

We took a slim lead into halftime, and with the deteriorating weather likely benefiting our running style of play in the second half, my apprehension turned to cautious optimism. Like many great Bridgeport teams before them, this one relied on its stout defense to make that lead stick for a hard-earned 14-13 victory. If I’d been there when the clock finally ticked down to zero, I’d have run onto the field and done snow angels.

As it was, the smile on my face as I gazed out over Haleakala’s otherworldly, Mars-like landscape had nearly as much to do with events back home as it did with the beauty right in front of me. Always a bit Indian-obsessed, I’d experienced the most significant loss of my life a few months earlier. The consistency and familiarity of Bridgeport football helped me cope, proving that sometimes a game is more than just a game.

2014

We may have stolen one a year before our time in 2013, but that just meant we were the team to beat in 2014. As it turned out, having a bullseye on our backs didn’t matter. The only blemish on our record for the second straight year was at the hands of Wheeling Park, who upended us 14-10 in another tight contest. Surprisingly, our only other close game of the regular season was an early 14-7 victory over Lewis County.

We dispatched the usual suspects that often gave us fits—Robert C. Byrd, North Marion, and Fairmont Senior—by wide margins. The Tribe was rolling, but given how evenly matched the previous season’s championship game with Wayne was, I thought we’d surely be tested in a semifinal rematch, the historical significance of which I wrote about in my first article for Connect-Bridgeport. Instead, we cruised to one of our most lopsided victories of the season, winning 48-7 and punching our title game ticket.

When you’ve won as much as Bridgeport, there aren’t many chances to win anything for the first time, but the 2014 Indians had played their way into an opportunity to do something none before them had ever done—win back-to-back state championships. The closest we’d ever come was in 2001, playing in the championship game after winning it the previous year, but ultimately losing to the Poca Dots.

Where was I during this monumental Bridgeport football event? Back on the Hawaiian islands, of course, riding a mule down a steep sea cliff trail on Moloka’i to the infamous Kalaupapa leper colony. We’d won with me in Hawaii the previous year, so there was no way I was jinxing our good fortune, even if the trip cost me a small fortune. Okay, not really. My two Hawaii adventures were just a coincidence, but they make for a good bar story.

An even better story is the true one—that we won the game to repeat as state champions! The only thing missing was a bit of Hollywood-style drama in our 43-7 manhandling of Frankfort. We seemed to get stronger throughout the fall of 2014, peaking just as the playoffs rolled around, distancing ourselves from the rest of the field, and leaving no doubt about who was the king of the Class AA mountain.

2015

The moment you let yourself believe there’s no way you can lose is often the same moment that dooms you to a crushing upset. Nevertheless, I knew we were going to win this one—the three-peat coronation of a dynasty—and I had to be there to witness it with friends. So off I went from Philadelphia to Wheeling, roughly a five-hour drive for a normal person but pushing seven for me, to meet up with a couple of other Bridgeport fanatics, Carl Correll and Alecia Ford.

But before we get there, let me tell you about a lightning bolt. By the time the calendar turned to 2015, I was a happy camper about the state of Bridgeport football, but I was also tired of losing to Wheeling Park. Those Class AAA bullies had prevented us from achieving perfection in 2013 and 2014, and I was ready to see us give them their comeuppance. I circled the early-season home date on my calendar and planned my trip from Philadelphia.

How’d that work out for me? Well, it started fine. I found a high seat where I could see all the action and watched us throw the better early-round punches. Although we hadn’t scored, we controlled the line of scrimmage and moved the ball well. Conversely, they ran into an impenetrable wall.

I felt good about possibly wearing them down as the game progressed and picking up yardage in bigger chunks. It was already starting to happen on our current drive, and then lightning struck, literally. A big bolt lit up the sky, and the referees immediately delayed the game. After several more flashes over the next thirty minutes, they called it.

What’s the big deal? The entire season is still in front of you. Record the tie and move on. And that’s exactly what we did. In fact, we had only one close game the rest of the way—a 28-20 semifinal playoff victory over Fairmont Senior in our second meeting with them. We shut out Tolsia 39-0 in the championship game as my friends and I spent most of the second half cutting up and holding a little mini-reunion in the stands.

But something ate at me afterward. Heck, it’s still eating at me today. I bet Dylan Tonkery, Dante Bonamico, Elijah Drummond, and the rest of that talented group also think about it occasionally. Here’s the rub: Wheeling Park won the Class AAA state championship that year. We were better than they were. I know it in my heart because I saw it with my eyes.

Wouldn’t it have been awesome to beat the AAA champs in the same year as we won AA? Has that even ever happened? I don’t know, but it’s exactly what we’d have done if that stupid lightning bolt hadn’t crashed through the night sky and robbed us of the “All-Class” title.

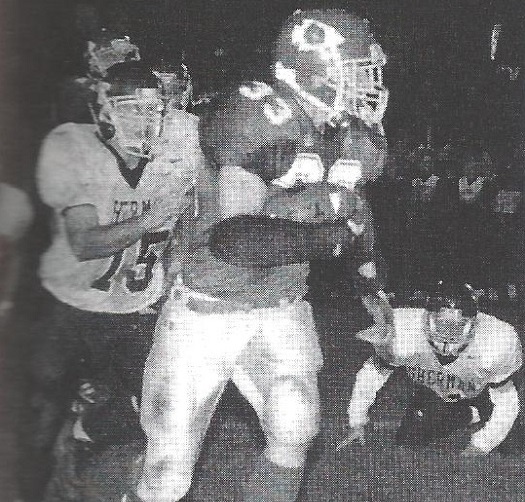

2019

“Neighborhood Kid Becomes a Champion by Reverting to an Old Offense and Leaning on a Special Player.” Where’s my editor when I need her to tighten up my wordy headline? Regardless, that’s my description of an iteration of the Indians that I’ve written about before and remember fondly, possibly because this group echoes the hard-nosed 1986 squad.

I’ve mentioned the names of a few individual contributors throughout this retrospective, but I’ve done so each time reluctantly. Football is a team sport. To be effective, any runner needs a powerful line opening holes in front of him. Nevertheless, we’ve all seen players who could make an extra defender miss or push the pile forward an extra yard.

The 2019 team had such a player in Carson Winkie. Come playoff time, they rested their fortunes on his broad shoulders even more heavily than they had during the regular season. Spoiler: he rose to the occasion in a way that reminded me of John Riggins, a favorite NFL player during my youth, who, with the help of a great offensive line, carried the Washington Redskins (Commanders today) on his back in a magical championship march.

But a few important pieces had to fall into place for him to do it. First, he had to get the opportunity. That wouldn’t have happened without a key coaching decision by John Cole, a kid who grew up three doors up from me on Vista Drive and who now happened to be the Head Coach. At some point late in the season—my old man’s memory is failing me here as to exactly when—Cole switched us from the pistol offense to the stick-I.

He was intimately familiar with the stick-I from his playing days under Coach Jamison. Lining up in it exclusively throughout the 1970s and 1980s, Jamison had made Bridgeport notorious around the state for this basic formation. A spear-shaped alignment that roughly reminds me of the arrowheads on our helmets, it telegraphed our intentions to run the ball straight into the heart of the defense. Everyone might have known what was coming, but few could stop it. If they wanted to settle any debate over its effectiveness, the naysayers had only to look in our trophy case at Jamison’s four championship plaques.

Along with Cole’s stick-I switch, Brian Henderson, who’d compiled several 100-yard-plus rushing games earlier in the season as the featured back, unselfishly moved to upback to block for Winkie. With Henderson and appropriately-named fullback Trey Pancake in front of him to help the line open holes, the stage was set for Winkie to assume the lead role. And did he ever, rumbling for nearly 600 yards in four playoff games.

The adjustments Cole made were especially pivotal in the final against Bluefield. I’d read that they had five Division I commits on their roster. To my knowledge, we had none. We countered their athleticism with three long touchdown drives of fifteen-plus plays. By game’s end, we’d possessed the ball for thirty-two of its forty-eight minutes, and the scoreboard read 21-14 in our favor. If there’s a high school football hall of fame, Cole’s game plan deserves to be enshrined.

2024

This isn’t your father’s Oldsmobile. Fifty is the new thirty (points, not years). I could keep going, but I’ll spare you. What I’m getting at is that we’ve been putting up video game numbers ever since Coach Tyler Phares installed the single-wing offense. And 2024 was the year we broke the machine, behind perhaps the best offensive line we’ve ever fielded.

Here’s a jarring statistic: Morgantown was our only regular-season opponent to hold us under fifty points, and that was in a 49-0 shutout. Arguably, every game was decided by halftime, and I believe we were up by 42 points or more at some point in all of them, triggering the continuously running clock “mercy rule.” The only “what if” to lament for this outstanding group is that they were never tested. I can’t help pondering how they might have risen to the occasion in a close contest.

Statistics don’t always tell the whole story, but they do a pretty good job when outcomes are as lopsided as they were for the 2024 Indians. How about scoring an average of 57 points a game while giving up only 8? High school sports website MaxPreps ranked us as the third-highest-scoring offense in the entire country.

Rushing is kind of my thing. If it’s yours, too, you’re in luck. We ran for 5,446 net yards and 100 touchdowns, averaging over 10 yards per carry. That’s nearly 400 yards every time we took the field. We even threw 7 touchdowns for good measure. Never mind that that only matched our per-game average on the ground; it’s no small feat at Bridgeport.

Just a word about our opponent in the final, Herbert Hoover, before I continue with the adulation. I lived in Elkview for about a year in 2006 while working in Charleston. It was a nice community that reminded me of Bridgeport, only with thicker accents.

During a 2016 flood, the Elk River dumped seven feet of water into the high school, and FEMA declared the building a total loss. West Virginians are no strangers to adversity, but the way that community has battled back is admirable. When the matchup was set, I thought about how I used to jog on their track that washed away and how I might be rooting for them if they were playing anyone else—a reminder that we’re all connected, that we’re only adversaries on the field, and that our opponents aren’t our enemies.

Now, back to our regularly scheduled programming. Bridgeport placed a staggering twelve players on the Class AAA All-State football team. Six earned first-team honors, including the captains on both sides of the ball—Wes Brown as an offensive lineman and Josh Love as a defensive utility player. You can read about all of them HERE.

Maybe more individual honors are coming. There are still some big ones to be announced. But make no mistake, this was a complete team through and through with depth on both sides of the ball. We might have been able to field a second-string unit worthy of the playoffs. There aren’t any other superlatives I can offer that someone else hasn’t shared already. This was a phenomenal team; one for the ages that I hope you had a chance to see in person, like I did.

Honorable Mention

American culture celebrates winning above all else. Would you like to know who I think made up most of those quotes about second place being for losers? Not really? Well, it’s my article, so I’ll tell you anyway. Those who shout that silliness loudest probably never competed in anything, much less even sniffed a ring.

Enough sermonizing. My point is that we’ve fielded some fine teams that didn’t summit the mountain, and they deserve a better fate than to be forgotten. I’m betting you’ll see it my way after you’re more familiar with their stories.

1962

During my mid-1980s playing days, Coach Jamison reminded us each fall before the start of deer season not to skip practice to go hunting, assuring us he’d bench us if we did. We may have thought the punishment harsh, but we also weren’t aware of the backstory that likely influenced it. Reading Jeff Toquinto’s article about the 1962 season years later finally gave me some insight into Coach Jamison’s sordid history with hunting that wrecked our chances of winning a championship and left a bitter taste in his mouth.

At that time, the playoff field consisted of a scant two teams that met to decide the state title. Undefeated for the first time at 10-0, we needed only one bonus point to secure the number two ranking and a spot against Summersville (modern-day Nicholas County) in the championship game.

Fortunately, we were sitting pretty with an ace in the hole. Kingwood and Parsons were scheduled to play in a game that would deliver us that bonus point regardless of the outcome, since we’d beaten them both. As college football analyst Lee Corso says, “Not so fast, my friend.”

They went turkey hunting instead! Not only that, but rather than ruling (logically) that one team would have to forfeit, the WVSSAC said the game simply wouldn’t count. Keyser remained ranked second ahead of us and won the championship.

Part of the charm of West Virginia sports for me has always been that strange, often controversial things happen in our little neck of the woods that may not occur elsewhere. While this one was certainly controversial, it was anything but charming.

A compelling quote from a still-heated-all-these-years-later Coach Jamison put 1962 over the top and secured its Honorable Mention ranking: “I know anything can happen in a high school football game, but we would have won. We could have named the score against either team that played that year for the title.”

As Toquinto noted, Coach Jamison would never have made such an uncharacteristically bold statement if he weren’t certain it was true. And if it’s good enough for Coach, it’s good enough for Bridgeport’s faithful!

2001

The 2001 team earned the right to play for something no Indians team before them had been able to accomplish: a repeat championship. They did it with a perfect 10-0 regular season, followed by three playoff victories in which they outscored their opponents 129-33.

I stood on the sidelines for one of those playoff romps over Wyoming East and watched C. R. Rohrbaugh rumble by like a charging bull, passing not six feet in front of me on a long touchdown run. My uncle and I were also in Wheeling for the championship game a few weeks later when we had the misfortune of running into an underrated Poca squad on the front end of a mini-dynasty that would see them become the first Class AA program to win three straight football championships (2001-2003).

There’s no shame in finishing 13-1 or losing to a formidable opponent like the Dots. And as you’ve read, our time to match their accomplishments would come a decade later. Regardless, the 2001 team was the first to play themselves into a repeat opportunity, and we should remember the grit they summoned to get back to the title game after winning it the previous year.

2009

Coach Bruce Carey won one state championship in 2000 and might have won a couple more had we not been reclassified from Class AA to AAA for several seasons in the mid-2000s. The 2009 team, led by Wes Tonkery and Huff Award winner Alex Sutton, was a juggernaut. As one of the smallest Class AAA schools in the state, they galloped to a 10-0 regular season, scoring over 50 points five times. Then, David slayed two Goliaths, Parkersburg and George Washington, in the playoffs.

Regardless of the scheme—stick-I, pistol, or single-wing—Bridgeport offenses are known for running almost exclusively. Defensively, we focus on stopping our opponents from running and forcing them to pass, where we think we have a good chance to force a turnover. It’s a time-tested strategy borne out through absurdly long streaks of winning seasons and playoff appearances.

But, if we have anything resembling an Achilles heel, it’s the long pass, and that’s exactly what tripped us up in the semifinals—twice if memory serves—against the South Charleston Black Eagles. Despite physically controlling the line of scrimmage and rolling up over 300 rushing yards, we dropped a hard-to-swallow 25-28 decision.

The following week, we were home for turkey dinner or deer season or whatever else occurs in Bridgeport around this time of year besides a trip to the state finals. Meanwhile, they cruised to a 28-7 championship. While “what might have been” is interesting to ponder, “what actually was” was pretty darned good in 2009, too.

2016

Despite losing significant senior leadership to the 2015 graduating class, the 2016 squad rolled through a 10-0 regular season. I excitedly wrote about how they’d finally beaten Wheeling Park and then dispatched three ranked foes in a row to close the season, including a rare fourth-quarter comeback from a ten-point deficit to Keyser on the road. However, the way the season ended stung so badly that I’ve blocked a key play out.

While I remember that we came within a point of playing in our fourth straight state title game, losing 21-22 to Fairmont Senior on our home field in a semifinal rematch of a close regular season game that we won 17-14, the way it happened is sketchy in my mind. When Fairmont went on to lose the championship game handily, I rationalized that we’d have probably lost by an even wider margin and dismissed the whole affair.

This isn’t the first time I’ve coped with defeat in this odd manner. When we endured a heartbreaking semifinal loss the season after I graduated (1987) to Tucker County in double overtime on a frozen Buckhannon field, I salved my wounds with the championship outcome. Winfield, you see, annihilated the tuckered-out Tucker County squad.

But as Coach Jamison often lectured our team when I played, just because you beat Team A by thirty and they beat Team B by twenty doesn’t mean you’ll coast to a fifty-point victory over Team B. That might sound logical, but football outcomes are often anything but. You settle scores on the field. Ergo, perhaps we’d have fared better in the state title game in 1987 and 2016 than the teams who narrowly beat us and then got smoked.

With the perspective hindsight can provide, I’ve tried to unblock the ending to 2016. I think it was a questionable spot, leaving us short of a first down by inches on a key fourth-down play late in the game that undid us. If that’s the case, the officiating crew was undoubtedly doing their best to untangle a mass of bodies and find the ball. That’s football, and a bitter ending mustn’t be allowed to erase a fine season from memory.

Final Thoughts

To see that winning championships isn’t typical, even at Bridgeport, all you have to do is read between the lines. And by lines, I mean years. In several instances, it’s been over a decade between state titles. Sure, we’ve won our share, but many students complete their high school careers without ever experiencing the joy of winning the ultimate prize.

“I don’t get what the big deal is. It’s only high school football,” a few people (whose opinions I don’t care about) have said over the years. Let them continue groveling at the feet of the mess created by “name, image, and likeness” (NIL) marketing payments as currently structured, the transfer portal, exorbitant salaries, and the broken systems of the college and professional games. Leave high school football to those of us who appreciate the farm-to-table appeal of local fans filling the stands to cheer for players who grew up in our communities.

We should also be vigilant in protecting it. With so much money at stake, it’s only a matter of time until those next-level problems begin trickling down if they haven’t already. Middle school and high school players transferring to districts where they’ll get more “exposure” might be good for the individual’s scholarship opportunities in some cases, but it hurts not only the school the player transfers from but also the one he transfers to—by destroying competitive balance.

I’m not a policy-maker, so I don’t have solutions to what are undoubtedly complex problems. What I do know is that building a winning culture begins with things Bridgeport’s been doing for decades like teaching and ingraining fundamental skills in youth football. Once they reach high school, helping athletes level up through the weight training program will pay much bigger dividends on the field than looking for a quick talent influx from outside. In making these observations, I’m thankful to be preaching to the loud and enthusiastic Bridgeport choir.

As for those objectors who “don’t get it,” you’re right. You don’t. You’re not from my hometown. I’m not even sure my beloved Uncle gets it, but I enjoyed trying to convince him over the years. He’s ninety now, so we won’t make it to another championship game. The memories of the three we attended together and the one I played in, which he also attended, will have to be enough for me. I’m pretty certain four are more than enough for him!

Congratulations, 2024 Indians on a season and team to remember alongside all the other great ones. I’ll let someone else rank them. Like a parent, I love all my children equally, both for their many similarities and the unique differences that make each one special. That’s my story, and I’m sticking to it.

Let’s get number twelve next season so I can lead with a proper The Twelve Days of Christmas analogy. Merry Christmas, Bridgeport!

An earlier version of this article is published in two parts on Connect Bridgeport HERE and HERE. Along with other minor updates, I added profiles of the 1962 and 2016 seasons to the Honorable Mention section.

Leave a comment